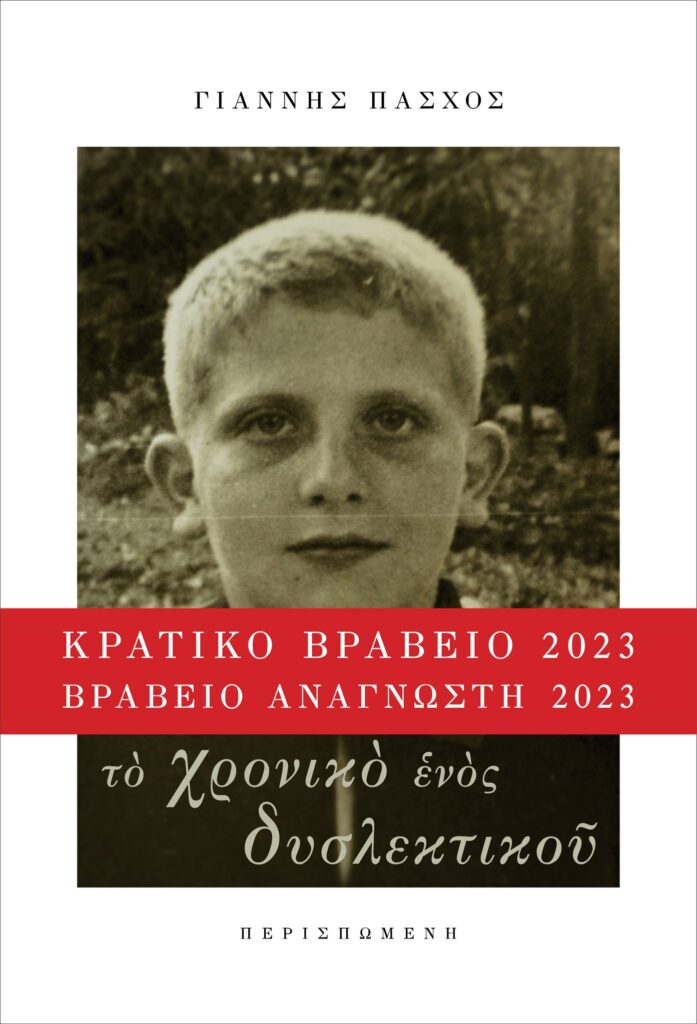

Chronicles of a Dyslexic

Novella

A child of teachers, Giannis Paschos was raised surrounded by books, and started writing as soon as he was could, not daunted by the fact he didn’t yet know the alphabet, his imagination transcending this small technicality. His parents’ attempted to move him from hieroglyphics to letters was a struggle, however.

He returns to, and takes the reader through, his time in school; where, when he tried to spell out a word, it felt as if the letters banged fiercely against each other, to then beam up, disappearing, describing it “a torture, a war”. Bookending his experience was his parents’ polarised approach to his education: a strict, traditional father, who suspected laziness, and a more relaxed, nurturing mother, who rejected the sedatives prescribed to ‘manage’ Giannis. He recalls and reflects on the resulting fractiousness, as they became increasingly worried about his struggles in school, where they both taught.

Desperate to unlock the skill, Giannis became determined to learn how to read in Year 2, locking himself away, fervently practising, with no insight or understanding as to why it was so difficult for him. Later he became inspired by his countryside surroundings to start composing poetry; the artistry in him keen to come to the surface, despite the challenge to capture it in written words. Despite his efforts, school became a slog and in Year 8 he began to wonder about what the point of school was, something that tormented him, but he made it to secondary school, as the entry exams were abolished just before he needed to do them, allowing him to get it. The university entrance exams still had to be faced, and he looks at the hyper-effort involved to navigate an academic system that didn’t have the scope to accommodate the learning challenges dyslexic people face. But against all odds, he got in on the second round, a testament to the work he’d put in and self-belief he’d had.

In university, he had a revelation: “The gaps in my learning and my related issues would never leave me, never in all my life, and the only way to move forward was to allow my critical thinking to gain some ground by using it as a bridge leading to the essence of things, over my learning gaps, which meant that I would have to combine much more parameters than anyone else to come to a decision.”

He graduated from the Biology department with a ‘very good’, before doing his military service, which is compulsory in Greece, staying with the army for twenty-eight months. Having taken us through his childhood and university days, he offers us an insightful reflection on his experience.

Page 1: My father was a teacher, my mother was a teacher, my uncle was a teacher, my auntie a teacher, my other uncle was a teacher, my maternal grandpa was a teacher, my parents’ friends were teachers, everyone in the world was a teacher and they all gave me advice, encouraging words and made wishes. The most popular wish was: “May you turn out to be like your uncle Agathocles”. My uncle Agathocles was a Greek expat in Canada. He was a dean at a university in Toronto and he was considered a brilliant role model for our wider family, until one day it was discovered that he lived with a male Korean ex-tennis player and he was, therefore, automatically defrocked. My deeply pious auntie made all his photos disappear from any family album but I, completely clueless about the grownups’ sadness and disappointment caused by the defrocking of our family’s idol, couldn’t stop asking them all when uncle Agathocles would be back so I could see in real life to whom I was supposed to look up to and wracked everyone’s nerves.Our house was full of books, everyone sounded like a teacher, everyone was always either reading or writing. So, I started writing before it was time for me to learn the alphabet. I wrote ceaselessly, like the grownups did. The main source of my inspiration was, as I recall, a big, thick illustrated American hardback scrapbook containing magical photos. Things I had never seen before: humongous machinery, lofty trees, impressive cars and enormous trucks. I had found this scrapbook amongst the things that were in my Ountra[1] package distributed to every pupil in our village. The package also contained a wedding dress, two ice skates, a cowboy’s gilet, a doll in a gingham dress and ten little lead soldiers. I would leaf through the scrapbook and describe in detail in writing what I saw, insisting not on what was there, but on what materialized in my head, on things that could not fit on the page of the scrapbook, those things that had run away and could be now found elsewhere.Those were the things I would describe in my own alphabet, and there was so much to be written down that I would fill whole hardback notebooks of 100 pages, that looked like a grocer’s ledger. Yes, my writing resembled hieroglyphics, characterized by the fact that it incorporated random, yet completely consecutive shapes, suffocatingly stuck on each other, and none of them was the same as any other. In order to make my writing more complex and cuter, I would toss in anything I could think of: a sun, a house, a cat’s head, a thunder, a foot.My obsession with endless writing and filling in notebooks with the shape-letters I had invented, troubled my parents. Perhaps, being teachers, they had thought to themselves that I would have an aptitude for the letters and, when they asked me what it was that I was writing so religiously, I pretended to read to them until -it goes without saying- mutual weariness, to the extent that more than once they had fallen asleep on our couch tired, one on top of the other, while I went on narrating, undaunted. All this took place a while before I went to reception. Τranslation: Alexandra Samotharki [1] Greek corruption of UNRRA (United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration