New

TAILS

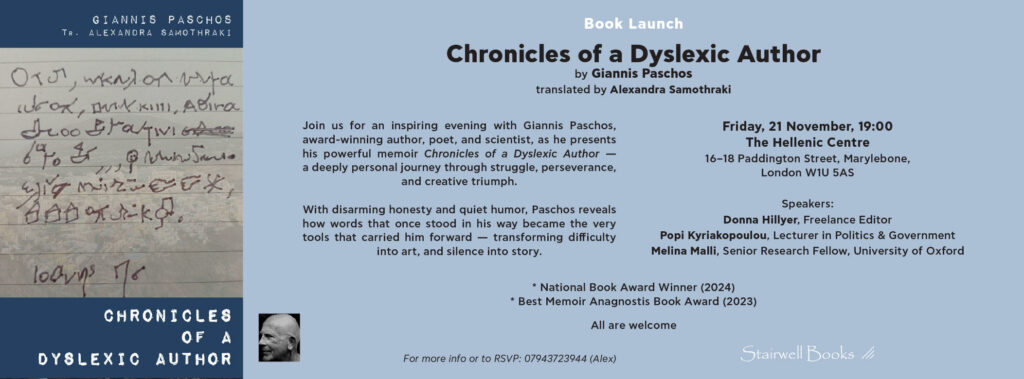

Friday,21 November, 19.00 , The Hellenic Center , London

The wolf

Alas to myself, for within me lies the deepest darkness of the night[1]

The whole village kept talking about the wolf. But no one had ever seen him. Neither the farmers working at their fields, nor the hunters that combed the forest and the surrounding mountains had chanced upon him or found a trace of his existence. Only his howling could be heard coming at times from the depths of the forest’s heart and yet at other times from the side of the village near the cemetery and the little church. No one had seen him when awake, but everyone had seen him in their sleep; some people dreamed of him with a disproportionately to the rest of the body big head that took up the whole frame of the dream, others only saw a row of sharp teeth, whiter than life like blood dripping stalagmites and others still saw themselves in his belly, as if they were one of his vital organs and through his eyes they could notice their petrified self, staring at the approaching wolf. However, some people only dreamt of the wolf as a small, cute, harmless bunny and themselves as a Cyclops eyeing each other motionless with no one taking the first step forward or back.

Stories about the wolf could usually be heard at the village’s coffee shop and spread like wildfires on the days when visitors came to the village for the Easter holidays. They brought with them their own speculations, thoughts and assumptions. The most educated among them described the wolf with precision and certainty, while little children were prompted by the grown ups to draw him. Kids had the chance to live their familiar fairy tales with the Big Bad Wolf and played several games as, unlike in the cities they came from, here they enjoyed abundant space and hiding places.

On Palm Sunday all those conversations came to an end and the coffee shop was filled with life, loud voices and singing. On Holy Tuesday, traditional belly dancing music such as “Madouvala” by Greek legend Stelios Kazantzidis and “Set the Place Alight” by Vagelis Gourlias could be heard until the break of day. In the middle of the Holy Week, people were letting out steam, away from the unnatural cities where they resided the rest of the year. They stuffed their faces with food, swallowing each bite whole regardless of what it was – pancetta, cheese pies, pancakes, pittas, tarhana soup, fresh eggs and warm bread. Then, children and grown ups alike, folded their arms on the tables and fell asleep, in pure bliss, among the cheeses and the butter, while older people were tearful with nostalgia.

On Easter Eve, everyone gathered, happy and glorious, at the small church, at the end of the village, near the forest: little girls in frilly dresses with their dolls, little boys holding miniature ships and cars and mums, especially mums, in their special, super festive edition of backless gowns despite the piercing, mid- April cold. The spring could be sensed culminating everywhere: smells, flower buds about to pop, violets and tulips. You could feel the earth breathing, sap filling the barks, life coming out of everywhere.

When it was almost time to celebrate the resurrection with great reverence, at the exact same moment when the priest called to his congregation to come forth and receive the holy light, at the exact same moment, the wolf’s howling was heard. People, holding on to their lighted candles, froze like wax themselves as the light flickered. Some of them even made a move to seek refuge in the tiny church.

The priest, on his rickety, wooden raised platform in front of the church, kept chanting undeterred while the village kids rang the bell and set off fireworks.

Suddenly, a huge, old wolf appeared through the trees. People stuck on each other without even realizing it and turned their lighted candles towards him like javelins. The wolf, obviously frail, sat on his two back legs, lifted his head as far as he could and let out his last terrible howling before collapsing on his side.

The priest stopped the service and the children stopped with their fireworks; time itself had stopped. But when the congregation was certain that the old wolf was too weak to stand on its legs, they started throwing at him, with no reserve whatsoever, as if they were possessed, without the slightest drop of mercy, their lightened, easter candles, as the children shouted and clapped and rang the bell with even more passion, while the old animal burnt. (Trans. Alexandra Samothraki)

[1] From the Troparion of Kassiani, an ecclesiastic hymn read during the evening service of Holy Tuesday, written by Kassiani, an abbess, poet, and composer in 9th century Byzantium.

Birds of paradise, December 2024

The Brussels Review: thebrusselsreview.com/giannis-paschos/the-feelings-detector

Translated by Alexandra Samothraki

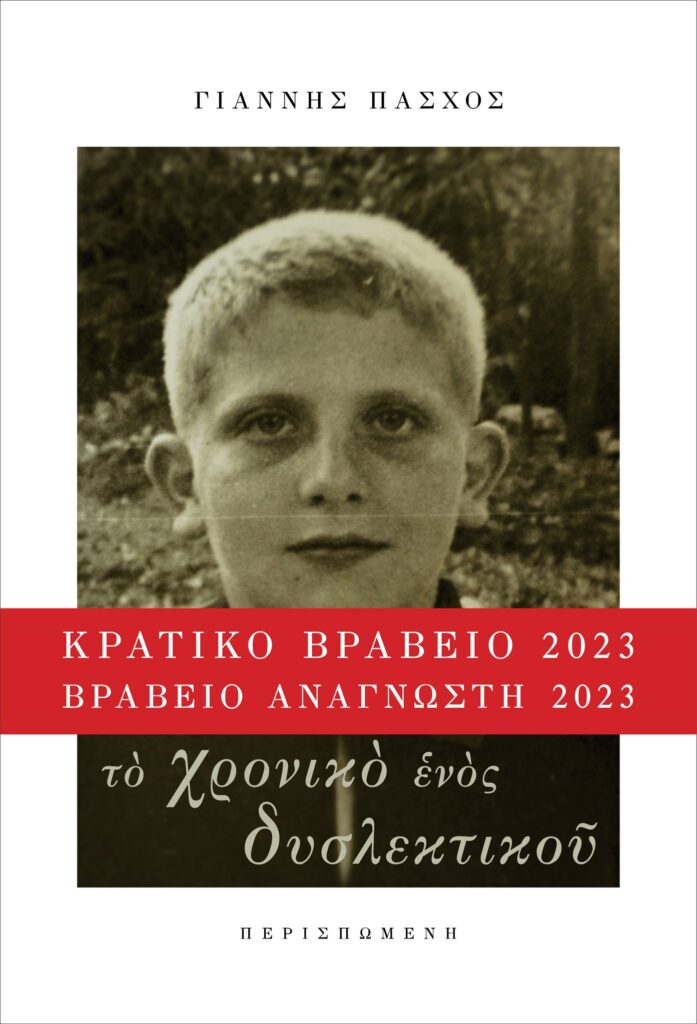

-Special National Book Award 2023 for promoting the dialogue on a sensitive matter, i.e. learning difficulties.

A child of teachers, Giannis Paschos was raised surrounded by books, and started writing as soon as he was could, not daunted by the fact he didn’t yet know the alphabet, his imagination transcending this small technicality. His parents’ attempted to move him from hieroglyphics to letters was a struggle, however.

He returns to, and takes the reader through, his time in school; where, when he tried to spell out a word, it felt as if the letters banged fiercely against each other, to then beam up, disappearing, describing it “a torture, a war”. Bookending his experience was his parents’ polarised approach to his education: a strict, traditional father, who suspected laziness, and a more relaxed, nurturing mother, who rejected the sedatives prescribed to ‘manage’ Giannis. He recalls and reflects on the resulting fractiousness, as they became increasingly worried about his struggles in school, where they both taught.

Desperate to unlock the skill, Giannis became determined to learn how to read in Year 2, locking himself away, fervently practising, with no insight or understanding as to why it was so difficult for him. Later he became inspired by his countryside surroundings to start composing poetry; the artistry in him keen to come to the surface, despite the challenge to capture it in written words. Despite his efforts, school became a slog and in Year 8 he began to wonder about what the point of school was, something that tormented him, but he made it to secondary school, as the entry exams were abolished just before he needed to do them, allowing him to get it. The university entrance exams still had to be faced, and he looks at the hyper-effort involved to navigate an academic system that didn’t have the scope to accommodate the learning challenges dyslexic people face. But against all odds, he got in on the second round, a testament to the work he’d put in and self-belief he’d had.

In university, he had a revelation: “The gaps in my learning and my related issues would never leave me, never in all my life, and the only way to move forward was to allow my critical thinking to gain some ground by using it as a bridge leading to the essence of things, over my learning gaps, which meant that I would have to combine much more parameters than anyone else to come to a decision.”

He graduated from the Biology department with a ‘very good’, before doing his military service, which is compulsory in Greece, staying with the army for twenty-eight months. Having taken us through his childhood and university days, he offers us an insightful reflection on his experience.